|

Look in a mirror. What do you see? A human? Self-confident, we tell ourselves that we are a gifted species that can see further than any other. And, because of big brains, we are probably right. But smart as we are, we have a lot to learn. John

R. Skoyles and Dorion Sagan, Up from Dragons

|

|

Many behavioral differences exist between chimps and humans, just as between chimps and gorillas or between gibbons and orangutans. But we are struck by how much the core of chimpanzee social life in the wild resembles some forms of human social organization, especially under great stress—in prisons, say, or urban and motorcycle gangs. or crime syndicates, or tyrannies and absolute monarchies. Niccolò Machiavelli, chronicling the maneuvering necessary to get ahead in the seamy politics of Renaissance Italy—and shocking his contemporaries, especially when he was honest—might have felt more or less at home in chimpanzee society. So might many dictators, whether they style themselves of the right or left persuasion. So might many followers. Beneath a thin varnish of civilization, it sometimes seems, there's a chimp struggling to bust out—to take off the absurd clothes and restraining social conventions and let loose. But this is not the whole story. Carl

Sagan and Ann Druyan, Shadows of Forgotten

Ancestors

|

The widely

renown Renaissance thinker, Niccolò Machiavelli,

was a Florentine statesman, writer, and political theorist.

Following his retirement from public service, Machiavelli

wrote at

length on the skill required for successfully running the state.

He is best known for his political treatise The

Prince, a short instruction book for

rulers that

attempts to lay out methods to secure and maintain political power.

Offering somewhat cynical recommendations, Machiavelli was

prescient in his realization that an individual's success is often most

effectively promoted by seemingly altruistic, honest, and prosocial

behavior. Although Machiavelli was one of the most brilliant and

original thinkers of the Renaissance, his name became synonymous with

deviousness, cruelty, and willfully destructive rationality. The

adjective "Machiavellian" emerged as a pejorative designation used to

describe those who manipulate others in an opportunistic and deceptive

way.

But

Machiavelli was not alone in history. The Arthashastra , a

treatise written in Sanskrit which means "the Science of Material Gain"

or "Science of Polity," discusses theories and principles of governing

a state. The Arthashastra is

distinguished by its

unabashed advocacy of "realpolitik." The original

author, Chanakya, who was a

Brahmin minister under Chandragupta

Maurya,

advocated that the ruler should use any means to attain his goal and

his actions required no moral sanction. He has often been

likened

to Machiavelli by political theorists, and the name of Chanakya is

reminiscent of a vastly scheming and clever political adviser. But

Machiavelli was not alone in history. The Arthashastra , a

treatise written in Sanskrit which means "the Science of Material Gain"

or "Science of Polity," discusses theories and principles of governing

a state. The Arthashastra is

distinguished by its

unabashed advocacy of "realpolitik." The original

author, Chanakya, who was a

Brahmin minister under Chandragupta

Maurya,

advocated that the ruler should use any means to attain his goal and

his actions required no moral sanction. He has often been

likened

to Machiavelli by political theorists, and the name of Chanakya is

reminiscent of a vastly scheming and clever political adviser.  Prior

to the surge of

field studies of primate behavior in the 1950s and 1960s, the

foundation of human intelligence was thought to lie in the challenge of

tool making. But observational studies in the wild and in naturalistic

zoological colonies induced a growing realization of the sophistication

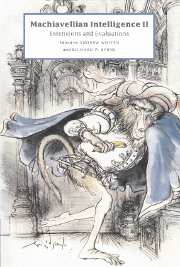

of social intelligence in primates. An interesting pair of

books

bearing the title Machiavellian

Intelligence present striking evidence of primate social

complexity. The books' titles were inspired by Franz de Waal's work, in

which he explicitly compared chimpanzee social strategies with the

advice offered four centuries earlier by

Machiavelli. An

intriguing account of a tangled social web in which

chimpanzees

live is incorporated in Franz de Waal's book Chimpanzee

Politics, which recounts de Waal's astute

observations

of the chimpanzee colony at the Burgers' zoo in Arnhem; de

Waal

describes episodes of ambition, social manipulation, sexual privileges

and power takeovers that could be attributed to human personalities,

but were preformed by (Machiavellian-minded) chimpanzees.

The contemporary understanding exemplified

in these

recent titles suggest that the keen observations of human

political interaction portrayed in the work

of Chanakya

and Machiavelli have a foundation in the recognizable social

complexity of humanity's closest primate relatives.

The

correlation between

social skill, group complexity, and brain size gives strong support

But the

human species, which

has inherited its Machiavellian intelligence from ancestral

great apes,

has

been further transformed by evolutionary pressures over several million

years. A 3½ million year old footprint in East

Africa

indicates that bipedal human ancestors had clearly diverged from the

great apes. By 2 million years

ago, our

ancestors had larger heads and were somewhat

precocious; taller

and larger brained ancestors in the human lineage used symmetrical

pear-shaped tools (hand axes) 1.8 million years ago.

Over

this evolutionary period, the the human lineage developed a

capacity exhibited in nascent form by

chimpanzees - tool

making. ago, our

ancestors had larger heads and were somewhat

precocious; taller

and larger brained ancestors in the human lineage used symmetrical

pear-shaped tools (hand axes) 1.8 million years ago.

Over

this evolutionary period, the the human lineage developed a

capacity exhibited in nascent form by

chimpanzees - tool

making. Beginning about 200,000 years ago, a new technique called Levallois, which produced carefully shaped flakes and points of stone, was practiced. Approximately 100,000 years ago anatomically modern humans carried tool-making kits that enabled the manufacture of specialist tools. Around 60,000 years ago, Homo sapiens sapiens had appeared, producing yet more sophisticated artifacts—blade tools, clothing, body ornaments, etc. The process of becoming human has been effectively depicted in the following video: During the course of this evolutionary process—the Paleolithic Revolution - our species was transformed from polygynous vegetarian quadrupeds into bipedal, monogamous, linguistic, tool-using hunter-gatherers. The transition from great apes to humans can be epitomized graphically as follows:

Amid this transition, Machiavellian intelligence was augmented and complemented by the development of technical (tool-making) intelligence and language. |

||

|

As a consequence

of their evolutionary advent, human hunter-gatherers, as

foragers, became top

predators

who lived off the yield of their surrounding habitat. With their

tool-making skills and ability to communicate and organize themselves

into groups, early hunter-gatherers were able to explore and settle new

environments. Until about 30,000 years ago, early

humans

dealt with immediate problems: deciding which food to eat, how to

survive the winter, how to avoid dangerous animals, where to find

shelter. They

committed

themselves emotionally to a small piece of geography, a limited band of

kinsmen, and two or three generations into the future. Their mental

predispositions, like those of other animal species, were circumscribed

by the immediate horizon and by short-term problems. There

would

have been little point in worrying about the long term if immediate

threats such as predators and winter were not dealt with. committed

themselves emotionally to a small piece of geography, a limited band of

kinsmen, and two or three generations into the future. Their mental

predispositions, like those of other animal species, were circumscribed

by the immediate horizon and by short-term problems. There

would

have been little point in worrying about the long term if immediate

threats such as predators and winter were not dealt with. By 30,000

years ago, our

ancestors had colonized much of the planet. At the

peak of

the last ice age 20,000 years ago, they fabricated clothing and shelter

to survive the harsh conditions.

At the end of

the last ice age, when temperatures rose and the ice sheets receded,

plants and animals grew more abundant, and new areas were settled.

Foraging

humans had an impact

on their surroundings. By 11,000 years ago, intense hunting

and

expanding human populations contributed to the widespread destruction

of large quadruped mammals, such as the giant sloth, mastodon, mammoth,

and great elk. Hunting populations gradually intensified

their

subsistence by pursuing smaller animals; by fishing, collecting

shellfish, and exploiting other forms of aquatic life; and by making

plants of varied types and increasing part of their diet. By

10,000 years ago, groups of hunter-gatherers in the southwest Asia were

living in permanent settlements, harvesting wild cereals and

domesticating local animals, commencing the transition to human

agriculture (the Agricultural

Revolution ). Over the next 5,000 years

agriculture became

established independently in

China,

southeast Asia, Europe, Africa, Mesoamerica, South America, and North

America. China,

southeast Asia, Europe, Africa, Mesoamerica, South America, and North

America.The earliest agriculture was horticulture—the cultivation of small garden plots with hand tools such as digging sticks or hoes. Early agriculturists identified collections of plants and animals that could live with them in mutual advantage, forming human-centered biological communities that displaced species not immediately useful to humans. As agricultural populations grew, intensive cultivation of large fields emerged—eventually employing plows and draft animals. Since agriculture could support significantly

larger

populations, During the

past

5,000 years until recent centuries, the predominant

form

of social organization was the agrarian state, exemplifyed

by the

following attributes:

|

|

|

|

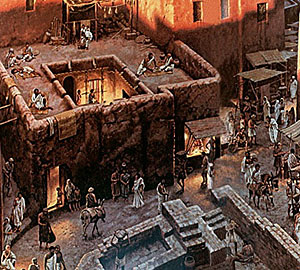

settlement sizes increased proportionately. Large groups

lived in

permanent villages, surrounded by material structures and goods

compatible with sedentary living. Specialized

craftsmen

emerged, supported by the community as a whole, to

meet the

community's new requirements—the beginning of social

differentiation.

settlement sizes increased proportionately. Large groups

lived in

permanent villages, surrounded by material structures and goods

compatible with sedentary living. Specialized

craftsmen

emerged, supported by the community as a whole, to

meet the

community's new requirements—the beginning of social

differentiation.