|

The Wisdom of AtonementInstructions, Study Guide, Practices

INTRODUCTION FOR FACILITATORS

|

Introduction for Facilitators

As indispensable as forgiveness has been throughout human history to the healing process, there has been another equally profound action vital to reconciliation, one that Arun Gandhi, grandson of Mohandas Gandhi, calls “the other side of the coin” of forgiveness. Turning over the coin of forgiveness, we discover atonement, the half-hidden, much-overlooked other half of the reconciliation process. Throughout history people have had to make difficult, even heartrending decisions about how to respond to the suffering they have endured at the hands of other human beings—or to the pain they themselves have inflicted upon other people. Over and over, we are confronted with the dilemma of how to respond to the cruelty and suffering that can pervade our lives. Do we forgive, or do we retaliate? Should we make peace or exact revenge? Can we live alongside our enemies, or do we seek retribution? And what about the harm we have caused? Is it possible for us to ever undo or make up for the damage we may have wreaked on the world? From the earliest times different cultures have resolved their conflicts and meted out justice in their own way.

Traditionally there have been two widely diverging paths—punishment or reform, which are rooted in retribution and forgiveness, respectively. The first is antagonistic and adversarial; the second, compassionate and cooperative. The difference between the two is dramatic. As the Chinese proverb has it, “If you are hell-bent on revenge, dig two graves”—one for your enemy and one for you. Revenge buries us in bitterness; hate immerses us in anger. While retaliation has earned the lion’s share of attention over the centuries, more measured responses to both personal and collective conflicts have also been practiced. The instinct to be vindictive may be as old as stone, but the impulse toward reconciliation runs like an ancient underground river. And like water dissolving stone, if it flows long enough, so too can acts of compassion dissolve anger, the showing of remorse prompt forgiveness, and the making of amends alleviate guilt. None of these paths is easy. Nor do we fi nd much encouragement, in a world riven by seemingly endless cycles of violence, to ask for forgiveness, still less to offer our own to someone who may have hurt us. But if we miss the moment for real reconciliation, we miss the chance to heal and move beyond the bitterness or guilt that can suffocate our lives.

Despite all the injunctions to exact revenge, from the hijacking of religious beliefs to testosterone-driven media violence, an impressive range of alternatives remains. Many distinguished scientists and philosophers now call into doubt the long-held belief that human beings are hardwired for violence. THE ROOT MEANING OF AT-ONE-MENT Dag Hammarskjöld, the Nobel Peace Prize laureate, said, “Forgiveness is the answer to the child’s dream of a miracle by which what is broken is made whole again, what is soiled is again made clean.” In the spring of 2009, Zainab Salbi, an Iraqi-American woman and founder of Women for Women International who works with women victims of war, said, “I think we need to forgive for our own health and healing. Without forgiveness, it’s hard to move on.”

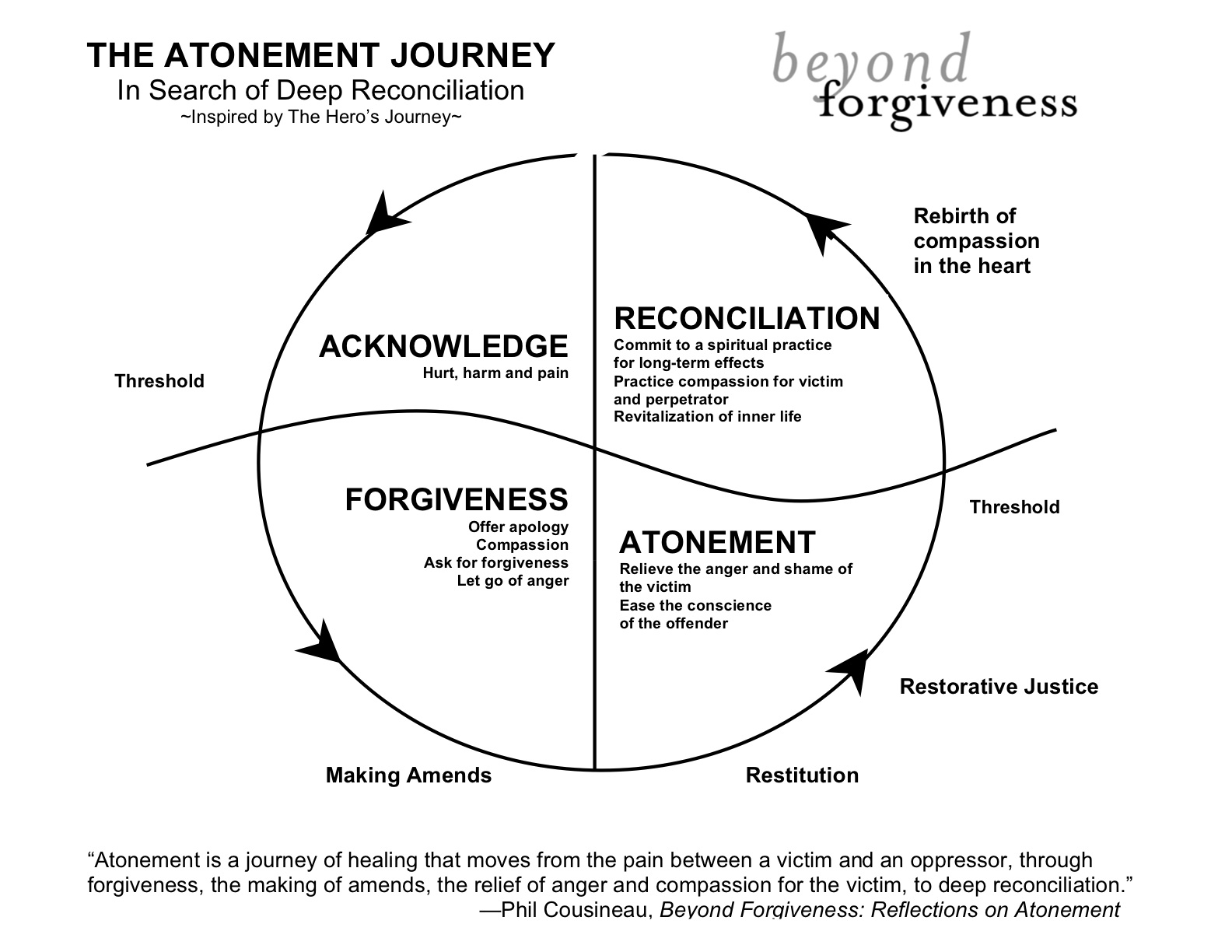

And yet there lingers a disturbing feeling. To forgive is noble; to be forgiven can be a reprieve. But surely there must be more to reconciliation between aggrieved peoples; otherwise, individuals, families, and entire cultures wouldn’t have been whiplashed by cycles of violence throughout history. Atonement is the act that proves the depth of our desire to be forgiven, or to forgive; it is the process of making things right, the restoration of some semblance of balance in our lives. Without offering those who wrong us, however seriously, the chance to make amends, or granting ourselves the opportunity to atone for any hurt we have caused, we remain stuck in the past; we suffer from a kind of “soul rust” and are unable to live fully in the present moment. The real work in conflict resolution is bringing these two practices of forgiveness and atonement together, whenever they have been split apart like cordwood, until we can say, in the spirit of the Irish bard Van Morrison, that “the healing has begun.”

Early in the fourteenth century, the word “atone” appeared in print for the first time. At that time it simply meant “to be in accord with, to make or become united or reconciled.” Two centuries later, the word was adapted and expanded by William Tyndale (1494–1536), a leader of the English Reformation and an early lexicographer. Tyndale had been frustrated by the lack of a direct translation of the biblical concept of reconciliation with God, and to better convey this core belief of his faith he combed ancient Hebrew and Greek manuscripts before finally combining two words, “at” and “onement.” Today, to atone generally means “to make amends for” but also carries connotations of being “at one with, in harmony.” Over time the understanding and practice of atonement has evolved from its theological underpinnings to more generally refer to an act that rights a wrong, makes amends, repairs harm, offers restitution, attempts compensation, clears the conscience of the offender, relieves the anger of the victim, and serves justice with a sacrifice commensurate with the harm that has been done.

What all the above stories, anecdotes, and reflections have in common can be compressed into a single observation that the late mythologist Joseph Campbell told Phil Cousineau in an interview, in 1985, which he felt was the core truth of all the great wisdom traditions throughout history: “The ultimate metaphysical realization is that you and the other are one.” Let us now embark on this healing journey of forgiveness and atonement together.

Study Guide

PREPARING THE LESSON

“The wise leader knows how to facilitate the unfolding group process, because the leader's process unfolds in the same way, according to the same principle.”

—John Heider, The Tao of Leadership

This study guide is intended to assist and inspire small group leaders in the practice of forgiveness and atonement by revealing various ways in which they can both contribute to personal and collective healing. The program is couched in a tone of process, and so it is recommended that you use as many questions about forgiveness and atonement as possible. In this manner you can direct the discussion and encourage as much active participation as possible, including the use of specific atonement practices, journaling and group discussion.

To facilitate this, we recommend that you draw out positive contributions, such as personal stories and recollections from history, literature, and movies. Consider yourself an atonement mentor, in the original sense of the word, which was “mind-maker,” someone who helps others “make up their own minds.” Your task is to help people find what is relevant and useful and inspirational about the role of atonement in the lives of your group, congregation, or ministry. Furthermore, it is suggested here that you help your group discover the deeper meanings of forgiveness and atonement in their own lives rather than judging how they themselves or others are practicing it. Be careful not to be judgmental about the amount of atonement someone has or has not performed in their own lives.

For example, instead of asking, “What does atonement mean?” which can be a very abstract question, ask, “What does atonement mean in our everyday life?” We highly recommended that every leader should have a copy in hand of Beyond Forgiveness, which has been described as “one of the most useful guides for long-lasting reconciliation” published in our time.

We highly recommend that you use the book, Beyond Forgiveness: Reflections on Atonement, by Phil Cousineau (Jossey-Bass, 2011; ISBN: 978-0-470-90773-3) for this course. For information on how to order the book please see this website:

www.wiley.com/buy/9780470907733

Seven Practices

Seven Practices of Atonement

1) Acknowledge the hurt, the harm, the wrong

2) Offer apologies, ask for forgiveness

3) Try to make amends commensurate with the harm done

4) Help to clear the conscience of the offender

5) Relieve the anger and shame of the victim

6) Practice compassion for victim and perpetrator alike

7) Establish a spiritual practice of prayer or meditation