Lev Kuleshov and his ‘effect’

Posted by keith1942 on September 10, 2009

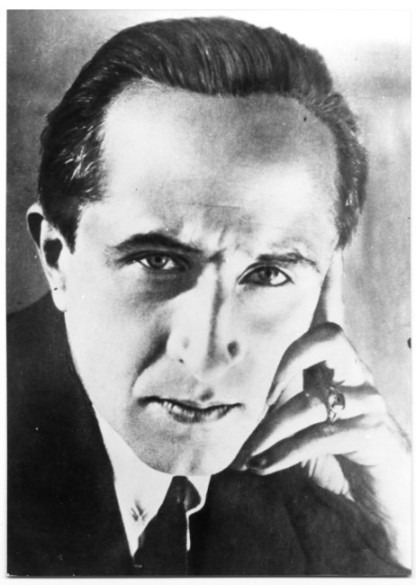

Lev Kuleshov (Cyrillic spelling Kulešov)

Il Cinema Ritrovato is an Archive Film Festival held annually in the Italian City of Bologna. For a week at the beginning of July about 900 enthusiasts watch films all day in three specialist cinemas. The Festival features both silent and sound films, and each year there are focuses on themes, movements and individual filmmakers. This year one of these was the early Soviet film director Lev Kuleshov. He is famous as the pioneer of what became known as Soviet Montage. Unfortunately, most of the time, his films are not that easy to see.

In 1929 three of his former students, including Vsevolod Pudovkin, proclaimed:

“We had no cinema before – and now it exists. The rise of cinema began with Kuleshov. Dealing with the questions of cinematic form was what was needed to start it off, and Kuleshov took up this task.” (Il Cinema Ritrovato Festival Catalogue).

Kuleshov’s fame and influence was mainly due to a series of famous experiments that he undertook, starting in 1920 in the Kuleshov Workshop. He had already worked in the pre-Revolutionary Russian cinema, with the noted director Eugenia Bauer. He was a fan of Hollywood techniques and very influenced by their [comparatively] rapid editing of the period. Kuleshov wrote extensively about his ideas and experiments. In 1921 he set about creating a non-existent city. (This short sequence was screened at the 1996 Pordenone Silent Film Festival).

”A few years later I made a more complex experiment: we shot a complete scene. Khokhlova and Obolensky acted in it. We filmed then in the following way: Khokhlova is walking along Petrov Street in Moscow near the ‘Mostorg’ street. Obolensky is walking along the embankment of the Moscow River – at a distance of about two miles away. They see each other, smile, and begin to walk towards one another. Their meeting is filmed at the Boulevard Prechistensk. This boulevard is in an entirely different section of the city. They clasp hands, with Gogol’s monument as background and look – at the White House – for at this point, we cut in a segment from an American [USA] film, The White House in Washington.” (Kuleshov on Film, page 52).

Kuleshov also experimented with creating a non-existent human being. Then later he filmed probably his most famous experiment, which involved taking a close up of the actor Ivan Mozhukhin and intercutting this shots with [variously] a bowl of soup, a coffin and a child: these were ‘projected to an audience which marvelled at the sensitivity of the acting’. This editing technique has become known as the Kuleshov Effect, when the meaning in a series of shots arises from the actual juxtaposition rather than from the shots themselves. The phrase is often applied to all sorts of examples of editing. However, strictly speaking, Kuleshov’s technique should be distinguished from the effects of parallel editing, where the meaning arises from the narrative context of the film. [This is the type of editing pioneered by D. W. Griffith].

Kuleshov was not just concerned with editing, he believed that the key to effective filmmaking was in organisation. He placed great emphasis on the scenario.

“Thus, all work can be reduced to the establishment of various labour processes, since something is done with objects: violating or ordering their commonplace organisation, handling them either rationally or irrationally, the actor-mannequin acts out the processes of labour. The labour process, its mechanics; then, movement; then the ultimate material of cinema. Thus, the work of the scenarist must come down to the expression of a fable through the organisation of people interacting with objects, facilitated by the behaviour of the person and his reflexes.” (Kuleshov on Film, page 145).

He regarded his films as exercises in achieving the requisite level of organisation. He wrote in 1926,

“It must not be forgotten that up to now the accomplishments of our group should be evaluated only as a bill of fare of Soviet film technique – the skills of our craft – and not as finished films.” (Kuleshov on film, page 141).

He applied these comments to his first film The Project of Engineer Pright (Proekt Inženera Prajta, 1918). The Festival screened the surviving reels with reconstructed intertitles. The film, shot before the revolution, displayed Kuleshov’s interest in fast Hollywood cutting, and the popular detective genre.

A similar approach was applied to his most famous film, a 1924 silent feature, The Extraordinary Adventures of Mr. West in the Land of the Bolsheviks (Neočajnye Priključenija Mistera Vesta V Strane Bol’ševikov). Mr. West is a US capitalist visiting the Soviet Union on business. His head is full of the myths and exaggerations that the western media put out about the ‘seat of the red menace’. His hosts play a joke on these preconceptions; first pretending to have him ‘kidnapped’ by a gang of terrorists, and then ‘rescued’ by the G.P.O. These experiences cure Mr. West of his grotesque preconceptions. The film laid bare the contemporary anti-Soviet propaganda for comedy and satire, and the film was very successful with domestic audiences.

By the Law (Po Zakonu, 1926) is generally reckoned to be Kuleshov’s finest film. The production was extremely economical: Jan Leyda reckoned it was the cheapest production ever filmed in Russia, (Kino 1960). It is an adaptation of a story by Jack London set in the wilds of Alaska, (The Unexpected). A dispute among a team of gold prospectors leads to murder and then an attempt to impose the ‘Law’ through trial and punishment. The film seems to have a conventional narrative, but eschews the common mainstream aspects of continuity. Audiences will likely notice the angular construction in the staging, and oddities in plot. Kuleshov’s style of filming produced an incredible intensity in performance and presentation. Jan Leyda quotes Sergei Tretyakov:

“The mathematical precision of every gesture and movement contributes to the total effect of each character and episodes. Kuleshov taught in his workshop that the hands, arms and legs are the most expressive parts of the film actor’s body and we can observe their movements create as much of the film’s tension as does the facial expression.” (Kino page 213].

And the film was critically praised when it received overseas distribution. The presentation at the Cinema Ritrovato received the accolade of a screening in the Piazza Maggiore. This open-air venue housed several thousand people, with a giant screen, and a live piano accompaniment.

The Festival also featured Kuleshov’s sound films. The most interesting was The Great Consoler (Velikij Utešitel’, 1933]. This film intertwined three separate stories, taken from the life and writings of the O Henry (the pseudonym of W. S. Porter). A period that Porter spent in jail was intercut with two of his short stories, including the famous Alias Jimmy Valentine. The complexity of the drama and the editing was impressive. The soundtrack was not of great quality, and was affected as we were listening to an English translation from the Russian on earphones. But the most noticeable aspect of the film was it political treatment. Essentially Kuleshov and his colleagues contrasted the conventional closure of Henry’s stories with the real-life events. So in Henry’s story Jimmy Valentine enjoys a happy ending. In the actual film plot variant he does not. The effects of the latter spark the climax in the film, when the death of Valentine produces a violent rebellion among the prison inmates. Given the film was produced during the repression of the 1930s and on the eve of the official promulgation of Socialist realism, this was a brave as well as critical line to take.

In fact, Kuleshov suffered increasing criticism, notably for ‘errors of formalism’. This label of errant behaviour was one that a number of great soviet artists suffered in this period: notably Eisenstein, who had also studied under Kuleshov. Kuleshov’s film output declined. During the war he worked only for the Sojuzdetfil’m studio, which specialised in films for the young. These films were fairly conventional, but Kuleshov showed a clear aptitude for working with young people. Sibirjaki (1940) has this distinctive plot device: two young pioneers search for a pipe that once belonged to Uncle Joe (Stalin). After the war Kuleshov gave up direction and concentrated on teaching at the State Film School.

One of the studies of early Soviet film is subtitled ‘Crippled Creative Biographies’ (Master of Soviet Cinema by Herbert Marshall, 1983), which gives a sense of artistic failures and repression. This is rather one-sided. Whilst Kuleshov [like Eisenstein for example] suffered increasing frustrations and restrictions in the 1930s, it was the revolutionary society of the 1920s that gave him opportunities. His writings are extremely critical of the limitation of pre-Soviet cinema: which in fact shared certain conventional approaches with Socialist Realism. Like Eisenstein, Pudovkin, or Mayakovsky in the world of theatre, the revolution offered an opportunity to experiment, overturn conventions, and rethink the values of film.

Kuleshov’s legacy is safe in one sense, because his experiments are remembered in the phrase ‘Kuleshov Effect’. The likelihood is now, after the major retrospective in Bologna, that a much greater part of his film output will become available [on DVD at least]. The Festival retrospective was curated by Ekaterina Hohlova, Yuri Tsivian and Nikolaj Izvolov. Ekaterina is the granddaughter of Kuleshov and his wife and star performer, Aleksandra Hohlova. She appeared in many of Kuleshov’s film, and was especially compelling in By the Law and The Great Consoler. She also directed a 1930 film, Saša. This was a tale of a peasant woman struggles in the city, and it is an example of an early feminist film. Unfortunately this major retrospective did not always a positive response The Sight & Sound review of Il Cinema Ritrovato used the somewhat dubious critical terms of ‘pain’ and ‘pleasure’. Pain was Kuleshov and pleasure was Josef Von Sternberg, [featuring a number of films starring Marlene Dietrich]. I am also a fan of Dietrich, but I think the reviewer missed some alternative pleasures. He seems to have made the same mistake as some earlier figures made regarding Hohlova:

“she was mistreated by producers and studio bosses whose male instincts prompted them that more conventional beauties and less eccentric talents might attract more money to the box office.” (Festival Catalogue].

Kuleshov’s films do offer some of the pleasures of entertainment films, but they also offer striking characteristics absent from the latter.

Screening in the Piazza Maggiore

The Adventures of Mr. West in the Land of the Bolsheviks and By the Law are available on the Internet on NTSC VHS Videos. By the Law is coupled with Chess Fever (Vsevolod Pudovkin, 1925).

Kuleshov on Film Writings of Lev Kuleshov. Translated and edited with an introduction by Ronald Levaco. University of California Press, 1974.

Kino A History of Russian and Soviet Film by Jan Leyda, Third edition, George Allen & Unwin, 1983

Il Cinema Ritrovato Website is at www.cinetecadibologna.it/cinemaritrovato.htm.

[Thanks to them for providing film stills.]

The Kuleshov effect – Sophia Main said

[…] OLENINA, A., 2008. LEV KULESHOV’S RETROSPECTIVE IN BOLOGNA, 2008: AN INTERVIEW WITH EKATERINA KHOKHLOVA [viewed DEC 13 2018]. Available from: https://cinetext.wordpress.com/2009/09/10/lev-kuleshov-and-his/ […]