So usually I don’t post on items like this, but I don’t get enough readers for anyone really to get offended, and frankly this is just bizarre. A new Israeli film set to screen in Tel Aviv this weekend exposes the Nazi-themed porn sensation in Israel in the early 1960s. Not my field of expertise, but this looks to me like the relatively logical and easy to understand (if weird) result of a society deeply repressed and disturbed over a few issues, the holocaust in particular. And built-up repression always has the most unhealthy ways of surfacing. Talk of the holocaust was extremely taboo in Israeli society and a source of guilt and shame until at least the 1960s and continues until today. The diaspora Jews, the victims of the holocaust, were often viewed, whether fairly or unfairly, as weak to have allowed the Nazis to do what they did without offering much of an answer. That was the epitome of the problem to which Zionism was supposed to be the solution. Adolf Eichmann’s capture in Argentina by the Mossad in 1960, followed by his trial and subsequent hanging in Jerusalem finally opened the flood gates. Arguably trying Nazi war criminals for their crimes against the Jewish people followed by a national discussion is a healthier way to address this taboo subject than … viewing holocaust porn. Read for yourself, and don’t shoot the messenger:

Mentioning the unmentionable

(Jerusalem Post)

An awkward topic in almost any context, pornography is an even more uncomfortable subject when its consumers are Israeli and it features Nazis as objects of lust. But prison camp porn, regardless of how anyone feels about it now, proved a best-selling sensation in early 1960s Israel, just as the country began to come to grips with the scale of the Nazi genocide.

Desire and memory – and their suppression – form the inspiration of a fascinating new documentary by the director Ari Libsker, whose latest film, Stalagim, focuses on the Nazi-themed porn and screens Saturday at the Tel Aviv Cinematheque.

Sharp, compelling and not even a little erotic, the film takes its title from the German abbreviation for “stammlager,” the POW camps that served as the setting of the Hebrew-language porn.

While Stalag books differed in the details, they relied, the film notes, on stories that were simple and consistent: An Allied pilot, on a bombing raid over Europe, is forced to parachute into Nazi territory, where he is captured and sent to a Stalag to be beaten and sexually dominated by female officers of the SS. In many of the Stalags, the inmate eventually kills his captor and escapes, but not before the book describes the pair’s sexual encounters in lurid and often sadistic detail.

Clandestinely sold at Tel Aviv’s central bus station, Stalag books were the underground bestseller of their day, a Hebrew pulp fiction that simultaneously addressed two of the period’s most unmentionable topics: sex and the Holocaust.

Those taboos have long since broken down, but the young Jewish state of the 1960s remained a “puritan, conservative” place, the narrator observes early in the film. Young adolescents – the first Israelis born after the creation of the state – were often left to figure out sexuality on their own, while Jewish victimhood under the Germans was treated as a symbol of shame, a failure of those insufficiently Zionist to flee.

Stalag books, not coincidentally, dealt with both topics just as the first Israeli-born teens were coming of age, giving the genre a sort of double appeal for curious, information-deprived adolescents.

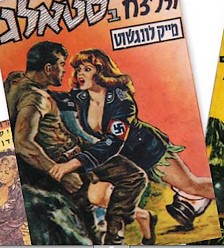

The books, whose covers frequently featured busty blondes with swastikas and weapons, took off in popularity not long after the start of the Eichmann trial in Jerusalem, the watershed event that brought the Final Solution into the open. Stalags would briefly break into the mainstream, with ads for the books appearing in major publications like Ha’olam Hazeh next to coverage of the trial.

But Stalags’ visibility also hastened their downfall, leading to efforts to have them banned as pornography. Copies of the most notorious of the books, I Was Colonel Schultz’s Private Bitch, were eventually tracked down and destroyed by the Israel Police, one of the film’s experts says.

On their own, the psychological, sexual and free speech issues connected with the books should capture Stalagim’s viewers. But the documentary, it turns out, also makes a number of interesting observations about sex and the way the Holocaust is memorialized today.

For although the Stalag genre might now be dismissed as merely a kitschy embarrassment of the past – an historical oddity on the path to Playboy and Penthouse – the film also calls attention to the writings of K. Tzetnik, the first Israeli writer to deal with the Holocaust. His 1953 novel, The House of Dolls, presented itself as the story of the author’s sister, a figure forced to work as a prostitute at Auschwitz’s infamous Block 24. For five decades a classic of Israel’s Holocaust literature, the book joined the national high school curriculum in the 1990s – and is itself now considered by academics pornographic and at least partially fabricated.

Why, the film wonders, should the Stalags be reviled and Tzetnik revered, when the former, if nothing else, were at least transparent in their fictional nature? (Among doubtful plot points in The House of Dolls is its placement of a Jewish woman in Auschwitz’s so-called “Pleasure Block.” Though the death camp indeed contained a brothel of sex slaves, and though Jewish women were indeed raped by the Nazis, German race laws prevented Jews’ inclusion at institutions designated purely for sex, even at Auschwitz.)

More provocatively, the film goes on, what is the nature of interest in the Holocaust, and how should the period be discussed in Israeli schools now?

With images of memorial ceremonies and school trips to Auschwitz in the background, one educator describes students’ “eager questions that become almost embarrassing,” while another says, “I’ll be frank. In a way, I make use of” students’ interest in the macabre.

Some viewers may bristle at hearing one Stalagim participant describe “Holocaust professionals” and “merchants,” but the film, which will also air Tuesday on Yes Docu, nevertheless concludes with several notable points.

Stalag books, it implies, sprang from repression, a society that believed history could be avoided and human urges ignored.

Two generations later, sex and the Holocaust are no longer taboo, having moved from the fringes to the culture’s mainstream. Young people carry fewer questions today than they did in the past, but do so in a society arguably consumed with sexuality and death. They’re better off, no doubt – but not as much, the film suggests, as this liberal society might want to believe.