Pain

Definition

Pain is an unpleasant feeling that is conveyed to the brain by sensory neurons. The discomfort signals actual or potential injury to the body. However, pain is more than a sensation, or the physical awareness of pain; it also includes perception, the subjective interpretation of the discomfort. Perception gives information on the pain's location, intensity, and something about its nature. The various conscious and unconscious responses to both sensation and perception, including the emotional response, add further definition to the overall concept of pain.

Description

Pain arises from any number of situations. Injury is a major cause, but pain may also arise from an illness. It may accompany a psychological condition, such as depression, or may even occur in the absence of a recognizable trigger.

Acute pain

Acute pain often results from tissue damage, such as a skin burn or broken bone. Acute pain can also be associated with headaches or muscle cramps. This type of pain usually goes away as the injury heals or the cause of the pain (stimulus) is removed.

To understand acute pain, it is necessary to understand the nerves that support it. Nerve cells, or neurons, perform many functions in the body. Although their general purpose, providing an interface between the brain and the body, remains constant, their capabilities vary widely. Certain types of neurons are capable of transmitting a pain signal to the brain.

As a group, these pain-sensing neurons are called nociceptors, and virtually every surface and organ of the body is wired with them. The central part of these cells is located in the spine, and they send threadlike projections to every part of the body. Nociceptors are classified according to the stimulus that prompts them to transmit a pain signal. Thermoreceptive nociceptors are stimulated by temperatures that are potentially tissue damaging. Mechanoreceptive nociceptors respond to a pressure stimulus that may cause injury. Polymodal nociceptors are the most sensitive and can respond to temperature and pressure. Polymodal nociceptors also respond to chemicals released by the cells in the area from which the pain originates.

Nerve cell endings, or receptors, are at the front end of pain sensation. A stimulus at this part of the nociceptor unleashes a cascade of neurotransmitters (chemicals that transmit information within the nervous system) in the spine. Each neurotransmitter has a purpose. For example, substance P relays the pain message to nerves leading to the spinal cord and brain. These neurotransmitters may also stimulate nerves leading back to the site of the injury. This response prompts cells in the injured area to release chemicals that not only trigger an immune response, but also influence the intensity and duration of the pain.

Chronic and abnormal pain

Chronic pain refers to pain that persists after an injury heals,

cancer pain, pain related to a persistent or degenerative disease, and long-term pain from an unidentifiable cause. It is estimated that one in three people in the United States will experience chronic pain at some point in their lives. Of these people, approximately 50 million are either partially or completely disabled.

Chronic pain may be caused by the body's response to acute pain. In the presence of continued stimulation of nociceptors, changes occur within the nervous system. Changes at the molecular level are dramatic and may include alterations in genetic transcription of neurotransmitters and receptors. These changes may also occur in the absence of an identifiable cause; one of the frustrating aspects of chronic pain is that the stimulus may be unknown. For example, the stimulus cannot be identified in as many as 85% of individuals suffering lower back pain.

Scientists have long recognized a relationship between depression and chronic pain. In 2004, a survey of California adults diagnosed with major depressive disorder revealed that more than one-half of them also suffered from chronic pain.

Other types of abnormal pain include allodynia, hyperalgesia, and phantom limb pain. These types of pain often arise from some damage to the nervous system (neuropathic). Allodynia refers to a feeling of pain in response to a normally harmless stimulus. For example, some individuals who have suffered nerve damage as a result of viral infection experience unbearable pain from just the light weight of their clothing. Hyperalgesia is somewhat related to allodynia in that the response to a painful stimulus is extreme. In this case, a mild pain stimulus, such as a pin prick, causes a maximum pain response. Phantom limb pain occurs after a limb is amputated; although an individual may be missing the limb, the nervous system continues to perceive pain originating from the area.

Causes and symptoms

Pain is the most common symptom of injury and disease, and descriptions can range in intensity from a mere ache to unbearable agony. Nociceptors have the ability to convey information to the brain that indicates the location, nature, and intensity of the pain. For example, stepping on a nail sends an information-packed message to the brain: the foot has experienced a puncture wound that hurts a lot.

Pain perception also varies depending on the location of the pain. The kinds of stimuli that cause a pain response on the skin include pricking, cutting, crushing, burning, and freezing. These same stimuli would not generate much of a response in the intestine. Intestinal pain arises from stimuli such as swelling, inflammation, and distension.

Diagnosis

Pain is considered in view of other symptoms and individual experiences. An observable injury, such as a broken bone, may be a clear indicator of the type of pain a person is suffering. Determining the specific cause of internal pain is more difficult. Other symptoms, such as fever or nausea, help narrow down the possibilities. In some cases, such as lower back pain, a specific cause may not be identifiable. Diagnosis of the disease causing a specific pain is further complicated by the fact that pain can be referred to (felt at) a skin site that does not seem to be connected to the site of the pain's origin. For example, pain arising from fluid accumulating at the base of the lung may be referred to the shoulder.

Since pain is a subjective experience, it may be very difficult to communicate its exact quality and intensity to other people. There are no diagnostic tests that can determine the quality or intensity of an individual's pain. Therefore, a medical examination will include a lot of questions about where the pain is located, its intensity, and its nature. Questions are also directed at what kinds of things increase or relieve the pain, how long it has lasted, and whether there are any variations in it. An individual may be asked to use a pain scale to describe the pain. One such scale assigns a number to the pain intensity; for example, 0 may indicate no pain, and 10 may indicate the worst pain the person has ever experienced. Scales are modified for infants and children to accommodate their level of comprehension.

Treatment

There are many drugs aimed at preventing or treating pain. Nonopioid

analgesics, narcotic analgesics, anticonvulsant drugs, and tricyclic antidepressants work by blocking the production, release, or uptake of neurotransmitters. Drugs from different classes may be combined to handle certain types of pain.

Nonopioid analgesics include common over-the-counter medications such as

aspirin, acetaminophen (Tylenol), and ibuprofen (Advil). These are most often used for minor pain, but there are some prescription-strength medications in this class.

Narcotic analgesics are only available with a doctor's prescription and are used for more severe pain, such as cancer pain. These drugs include codeine, morphine, and methadone. Addiction to these painkillers is not as common as once thought. Many people who genuinely need these drugs for pain control typically do not become addicted. However, narcotic use should be limited to patients thought to have a short life span (such as people with terminal cancer) or patients whose pain is only expected to last for a short time (such as people recovering from surgery). In August 2004, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) issued new guidelines to help physicians prescribe

narcotics appropriately without fear of being arrested for prescribing the drugs beyond the scope of their medical practice. DEA is trying to work with physicians to ensure that those who need to drugs receive them but to ensure opioids are not abused.

Anticonvulsants, as well as

antidepressant drugs, were initially developed to treat seizures and depression, respectively. However, it was discovered that these drugs also have pain-killing applications. Furthermore, since in cases of chronic or extreme pain, it is not unusual for an individual to suffer some degree of depression; antidepressants may serve a dual role. Commonly prescribed anticonvulsants for pain include phenytoin, carbamazepine, and clonazepam. Tricyclic antidepressants include doxepin, amitriptyline, and imipramine.

Intractable (unrelenting) pain may be treated by injections directly into or near the nerve that is transmitting the pain signal. These root blocks may also be useful in determining the site of pain generation. As the underlying mechanisms of abnormal pain are uncovered, other pain medications are being developed.

Drugs are not always effective in controlling pain. Surgical methods are used as a last resort if drugs and local anesthetics fail. The least destructive surgical procedure involves implanting a device that emits electrical signals. These signals disrupt the nerve and prevent it from transmitting the pain message. However, this method may not completely control pain and is not used frequently. Other surgical techniques involve destroying or severing the nerve, but the use of this technique is limited by side effects, including unpleasant numbness.

Alternative treatment

Both physical and psychological aspects of pain can be dealt with through alternative treatment. Some of the most popular treatment options include

acupressure and

acupuncture, massage, chiropractic, and relaxation techniques such as

yoga, hypnosis, and

meditation. Herbal therapies are gaining increased recognition as viable options; for example, capsaicin, the component that makes cayenne peppers spicy, is used in ointments to relieve the joint pain associated with arthritis. Contrast

hydrotherapy can also be very beneficial for pain relief.

Lifestyles can be changed to incorporate a healthier diet and regular

exercise. Regular exercise, aside from relieving

stress, has been shown to increase endorphins, painkillers naturally produced in the body.

Prognosis

Successful pain treatment is highly dependent on successful resolution of the pain's cause. Acute pain will stop when an injury heals or when an underlying problem is treated successfully. Chronic pain and abnormal pain are more difficult to treat, and it may take longer to find a successful resolution. Some pain is intractable and will require extreme measures for relief.

Prevention

Pain is generally preventable only to the degree that the cause of the pain is preventable. For example, improved surgical procedures, such as those done through a thin tube called a laparascope, minimize post-operative pain. Anesthesia techniques for surgeries also continuously improve. Some disease and injuries are often unavoidable. However, pain from some surgeries and other medical procedures and continuing pain are preventable through drug treatments and alternative therapies.

Resources

Periodicals

"Advances in Pain Management, New Focus Greatly Easing Postoperative Care." Medical Devices & Surgical Technology Week September 26, 2004: 260.

Finn, Robert. "More than Half of Patients With Major Depression Have Chronic Pain." Family Practice News October 15, 2004: 38.

"New Guidelines Set for Better Pain Treatment." Medical Letter on the CDC & FDA September 5, 2004: 95.

Organizations

American Chronic Pain Association. P.O. Box 850, Rocklin, CA 95677-0850. (916) 632-0922. 〈http://members.tripod.com/∼widdy/ACPA.html〉.

American Pain Society. 4700 W. Lake Ave., Glenview, IL 60025. (847) 375-4715. http://www.ampainsoc.org.

Key terms

Acute pain — Pain in response to injury or another stimulus that resolves when the injury heals or the stimulus is removed.

Chronic pain — Pain that lasts beyond the term of an injury or painful stimulus. Can also refer to cancer pain, pain from a chronic or degenerative disease, and pain from an unidentified cause.

Neurotransmitters — Chemicals within the nervous system that transmit information from or between nerve cells.

Nociceptor — A neuron that is capable of sensing pain.

Referred pain — Pain felt at a site different from the location of the injured or diseased part of the body. Referred pain is due to the fact that nerve signals from several areas of the body may "feed" the same nerve pathway leading to the spinal cord and brain.

Stimulus — A factor capable of eliciting a response in a nerve.

Gale Encyclopedia of Medicine. Copyright 2008 The Gale Group, Inc. All rights reserved.

pain

[pān] a feeling of distress, suffering, or agony, caused by stimulation of specialized nerve endings. Its purpose is chiefly protective; it acts as a warning that tissues are being damaged and induces the sufferer to remove or withdraw from the source. The North American Nursing Diagnosis Association has accepted pain as a

nursing diagnosis, defining it as a state in which an individual experiences and reports severe discomfort or an uncomfortable sensation; the reporting of pain may be either by direct verbal communication or by encoded descriptors.

Pain Receptors and Stimuli. All receptors for pain stimuli are

free nerve endings of groups of myelinated or unmyelinated neural fibers abundantly distributed in the superficial layers of the skin and in certain deeper tissues such as the periosteum, surfaces of the joints, arterial walls, and the falx and tentorium of the cranial cavity. The distribution of pain receptors in the gastrointestinal mucosa apparently is similar to that in the skin; thus, the mucosa is quite sensitive to irritation and other painful stimuli. Although the parenchyma of the liver and the alveoli of the lungs are almost entirely insensitive to pain, the liver and bile ducts are extremely sensitive, as are the bronchi and parietal pleura.

Some pain receptors are selective in their response to stimuli, but most are sensitive to more than one of the following types of excitation: (1) mechanical stress of trauma; (2) extremes of heat and cold; and (3) chemical substances, such as histamine, potassium ions, acids, prostaglandins, bradykinin, and acetylcholine. Pain receptors, unlike other sensory receptors in the body, do not adapt or become less sensitive to repeated stimulation. Under certain conditions the receptors become more sensitive over a period of time. This accounts for the fact that as long as a traumatic stimulus persists the person will continue to be aware that damage to the tissues is occurring.

The body is able to recognize tissue damage because when cells are destroyed they release the chemical substances previously mentioned. These substances can stimulate pain receptors or cause direct damage to the nerve endings themselves. A lack of oxygen supply to the tissues can also produce pain by causing the release of chemicals from ischemic tissue. Muscle spasm is another cause of pain, probably because it has the indirect effect of causing ischemia and stimulation of chemosensitive pain receptors.

Transmission and Recognition of Pain. When superficial pain receptors are excited the impulses are transmitted from these surface receptors to synapses in the gray matter (substantia gelatinosa) of the dorsal horns of the spinal cord. They then travel upward along the sensory pathways to the thalamus, which is the main sensory relay station of the brain. The dorsomedial nucleus of the thalamus projects to the prefrontal cortex of the brain. The conscious perception of pain probably takes place in the thalamus and lower centers; interpretation of the quality of pain is probably the role of the cerebral cortex.

The perception of pain by an individual is highly complex and individualized, and is subject to a variety of external and internal influences. The cerebral cortex is concerned with the appreciation of pain and its quality, location, type, and intensity; thus, an intact sensory cortex is essential to the perception of pain. In addition to neural influences that transmit and modulate sensory input, the perception of pain is affected by psychological and cultural responses to pain-related stimuli. A person can be unaware of pain at the time of an acute injury or other very stressful situation, when in a state of depression, or when experiencing an emotional crisis. Cultural influences also precondition the perception of and response to painful stimuli. The reaction to similar circumstances can range from complete stoicism to histrionic behavior.

Pain Control. There are several theories related to the physiologic control of pain but none has been completely verified. One of the best known is that of Mellzak and Wall, the

gate control theory, which proposed that pain impulses were mediated in the substantia gelatinosa of the spinal cord with the dorsal horns acting as “gates” that controlled entry of pain signals into the central pain pathways. Also, pain signals would compete with tactile signals with the two constantly balanced against each other.

Since this theory was first proposed, researchers have shown that the neuronal circuitry it hypothesizes is not precisely correct. Nevertheless, there are internal systems that are now known to occur naturally in the body for controlling and mediating pain. One such system, the opioid system, involves the production of morphinelike substances called

enkephalins and

endorphins. Both are naturally occurring analgesics found in various parts of the brain and spinal cord that are concerned with pain perception and the transmission of pain signals. Signals arising from stimulation of neurons in the gray matter of the brain stem travel downward to the dorsal horns of the spinal cord where incoming pain impulses from the periphery terminate. The descending signals block or significantly reduce the transmission of pain signals upward along the spinal cord to the brain where pain is perceived by releasing these substances.

In addition to the brain's opioid system for controlling the transmission of pain impulses along the spinal cord, there is another mechanism for the control of pain. The stimulation of large sensory fibers extending from the tactile receptors in the skin can suppress the transmission of pain signals from thinner nerve fibers. It is as if the nerve pathways to the brain can accommodate only one type of signal at a time, and when two kinds of impulses simultaneously arrive at the dorsal horns, the tactile sensation takes precedence over the sensation of pain.

The discovery of endorphins and the inhibition of pain transmission by tactile signals has provided a scientific explanation for the effectiveness of such techniques as relaxation, massage, application of liniments, and acupuncture in the control of pain and discomfort.

Assessment of Pain. Pain is a subjective phenomenon that is present when the person who is experiencing it says it is. The person reporting personal discomfort or pain is the most reliable source of information about its location, quality, intensity, onset, precipitating or aggravating factors, and measures that bring relief.

Objective signs of pain can help verify what a patient says about pain, but such data are not used to prove or disprove whether it is present. Physiologic signs of moderate and superficial pain are responses of the sympathetic nervous system. They include rapid, shallow, or guarded respiratory movements, pallor, diaphoresis, increased pulse rate, elevated blood pressure, dilated pupils, and tenseness of the skeletal muscles. Pain that is severe or located deep in body cavities acts as a stimulant to parasympathetic neurons and is evidenced by a drop in blood pressure, slowing of pulse, pallor, nausea and vomiting, weakness, and sometimes a loss of consciousness.

Behavioral signs of pain include crying, moaning, tossing about in bed, pacing the floor, lying quietly but tensely in one position, drawing the knees upward toward the abdomen, rubbing the painful part, and a pinched facial expression or grimacing. The person in pain also may have difficulty concentrating and remembering and may be totally self-centered and preoccupied with the pain.

Psychosocial aspects of tolerance for pain and reactions to it are less easily identifiable and more complex than physiologic responses. An individual's reaction to pain is subject to a variety of psychologic and cultural influences. These include previous experience with pain, training in regard to how one should respond to pain and discomfort, state of health, and the presence of fatigue or physical weakness. One's degree of attention to and distraction from painful stimuli can also affect one's perception of the intensity of pain. A thorough assessment of pain takes into consideration all of these psychosocial factors.

Management of Pain. Among the measures employed to provide relief from pain, administration of analgesic drugs is probably the one that is most often misunderstood and abused. When an analgesic drug has been ordered “as needed,” the patient should know that the drug is truly available when needed and that it will be given promptly when asked for. If the patient is forced to wait until someone else decides when an analgesic is needed, the patient may become angry, resentful, and tense, thus diminishing or completely negating the desired effect of the drug. Studies have shown that when analgesics are left at the bedside of terminally ill cancer patients to be taken at their discretion, fewer doses are taken than when they must rely on someone else to make the drug available. Habituation and addiction to analgesics probably result as much from not using other measures along with analgesics for pain control as from giving prescribed analgesics when they are ordered.

Patient-controlled analgesia has been used safely and effectively.

When analgesics are not appropriate or sufficient or when there is a real danger of addiction, there are noninvasive techniques that can be used as alternatives or adjuncts to analgesic therapy. The selection of a particular technique for the management of pain depends on the cause of the pain, its intensity and duration, whether it is acute or chronic, and whether the patient perceives the technique as effective.

Distraction techniques provide a kind of sensory shielding to make the person less aware of discomfort. Distraction can be effective in the relief of brief periods of acute pain, such as that associated with minor surgical procedures under local anesthesia, wound débridement, and venipuncture.

Massage and gentle pressure activate the thick-fiber impulses and produce a preponderance of tactile signals to compete with pain signals. It is interesting that stimulation of the large sensory fibers leading from superficial sensory receptors in the skin can relieve pain at a site distant from the area being rubbed or otherwise stimulated. Since ischemia and muscle spasm can both produce discomfort, massage to improve circulation and frequent repositioning of the body and limbs to avoid circulatory stasis and promote muscle relaxation can be effective in the prevention and management of pain.

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) units enhance the production of endorphins and enkephalins and can also relieve pain.

Specific relaxation techniques can help relieve physical and mental tension and stress and reduce pain. They have been especially effective in mitigating discomfort during labor and delivery but can be used in a variety of situations. Learning proper relaxation techniques is not easy for some people, but once these techniques have been mastered they can be of great benefit in the management of chronic ongoing pain. The intensity of pain also can be reduced by stimulating the skin through applications of either heat or cold, menthol ointments, and liniments. Contralateral stimulation involves stimulating the skin in an area on the side opposite a painful region. Stimulation can be done by rubbing, massaging, or applying heat or cold.

Since pain is a symptom and therefore of value in diagnosis, it is important to keep accurate records of the observations of the patient having pain. These observations should include the following: the nature of the pain, that is, whether it is described by the patient as being sharp, dull, burning, aching, etc.; the location of the pain, if the patient is able to determine this; the time of onset and the duration, and whether or not certain nursing measures and drugs are successful in obtaining relief; and the relation to other circumstances, such as the position of the patient, occurrence before or after eating, and stimuli in the environment such as heat or cold that may trigger the onset of pain.

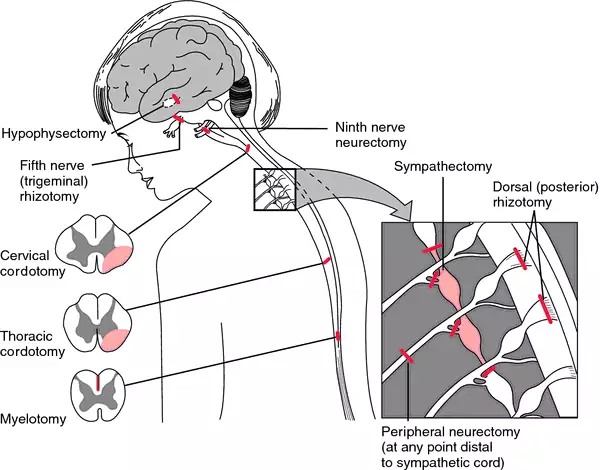

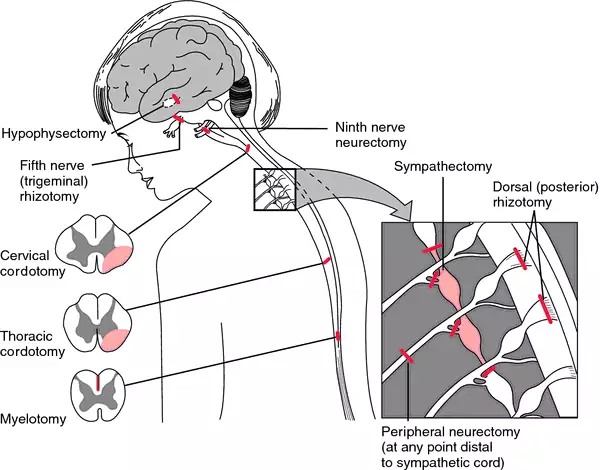

Surgical procedures designed to alleviate pain. From Ignatavicius et al., 1999.

acute pain 1. one of the three categories of pain established by the International Association for the Study of Pain, denoting pain that is caused by occurrences such as traumatic injury, surgical procedures, or medical disorders; clinical symptoms often include increased heart rate, blood pressure, and respiratory rate, shallow respiration, agitation or restlessness, facial grimaces, or splinting.

2. a nursing diagnosis accepted by the North American Nursing Diagnosis Association, defined as an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience arising from actual or potential tissue damage or described in terms of such damage, with sudden or slow onset of any intensity from mild to severe with an anticipated or predictable end and a duration of less than 6 months.

bearing-down pain pain accompanying uterine contractions during the second stage of

labor.

cancer pain one of the three categories of pain established by the International Association for the Study of Pain, denoting pain associated with malignancies and perceived by the individual patient; there are various scales ranking it from 0 to 10 according to level of severity.

chronic pain 1. one of the three categories of pain established by the International Association for the Study of Pain, denoting pain that is persistent, often lasting more than six months; clinical symptoms may be the same as for acute pain, or there may be no symptoms evident. The North American Nursing Diagnosis Association has accepted chronic pain as a nursing diagnosis.

2. a nursing diagnosis accepted by the North American Nursing Diagnosis Association, defined as an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience arising from actual or potential tissue damage or described in terms of such damage, with sudden or slow onset of any intensity from mild to severe, without an anticipated or predictable end, and with a duration of greater than 6 months.

pain disorder a

somatoform disorder characterized by a chief complaint of severe chronic pain that causes substantial distress or impairment in functioning; the pain is neither feigned nor intentionally produced, and psychological factors appear to play a major role in its onset, severity, exacerbation, or maintenance. The pain is related to psychological conflicts and is made worse by environmental stress; it enables the patient to avoid an unpleasant activity or to obtain support and sympathy. Patients may visit many health care providers searching for relief and may consume excessive amounts of analgesics without any effect. They are difficult to treat because they strongly resist the idea that their symptoms have a psychological origin.

growing p's any of various types of recurrent limb pains resembling those of rheumatoid conditions, seen in early youth and formerly thought to be caused by the growing process.

hunger pain pain coming on at the time for feeling hunger for a meal; a symptom of gastric disorder.

intermenstrual pain pain accompanying ovulation, occurring during the period between the menses, usually about midway.

labor p's the rhythmic pains of increasing severity and frequency due to contraction of the uterus at childbirth; see also

labor.

lancinating pain sharp darting pain.

phantom pain pain felt as if it were arising in an absent or amputated limb or organ; see also

amputation.

psychogenic pain symptoms of physical pain having psychological origin; see

pain disorder.

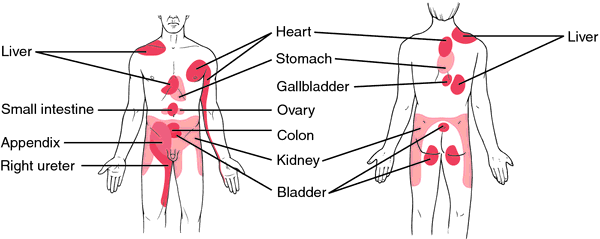

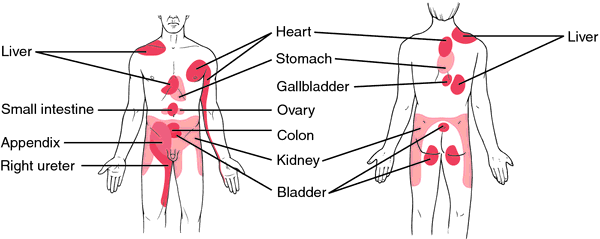

referred pain pain in a part other than that in which the cause that produced it is situated. Referred pain usually originates in one of the visceral organs but is felt in the skin or sometimes in another area deep inside the body. Referred pain probably occurs because pain signals from the viscera travel along the same neural pathways used by pain signals from the skin. The person perceives the pain but interprets it as having originated in the skin rather than in a deep-seated visceral organ.

Area of referred pain, anterior and posterior views.

rest pain a continuous unrelenting pain due to ischemia of the lower leg, beginning with or being aggravated by elevation and being relieved by sitting with legs in a dependent position or by standing.

root pain pain caused by disease of the sensory nerve roots and occurring in the cutaneous areas supplied by the affected roots.

Miller-Keane Encyclopedia and Dictionary of Medicine, Nursing, and Allied Health, Seventh Edition. © 2003 by Saunders, an imprint of Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved.